It’s 5:30am and Little Bay Beach in south-west Sydney is slowly coming to life. First come the swimmers. Two men in wetsuits gaze out across the still-dark ocean as if contemplating whether or not they’re about to make the right decision. After a few obligatory stretches, they slip quietly into the water before disappearing from view. Next, a young couple set up a picnic blanket and wait patiently for the sun’s arrival. (Which, according to our phone, should occur in precisely seven minutes.) One by one, more people come to complete their morning pilgrimage to the beach. There’s a stillness to the scene that, in a city like Sydney, can only occur at this hour – before deadlines, morning meetings and social media scrolling compete for our attention.

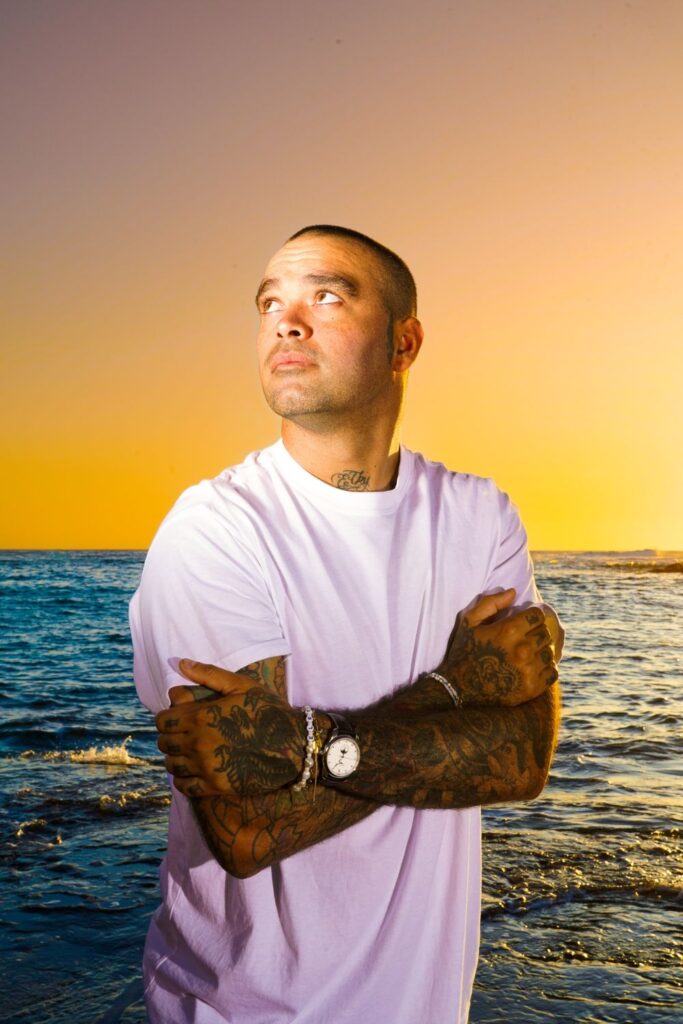

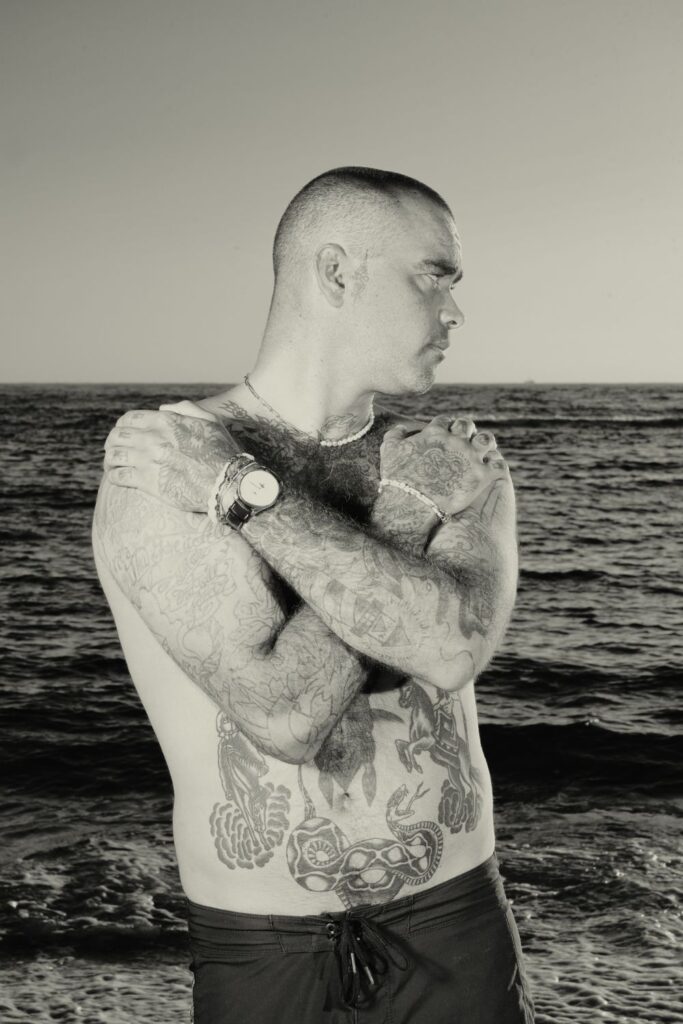

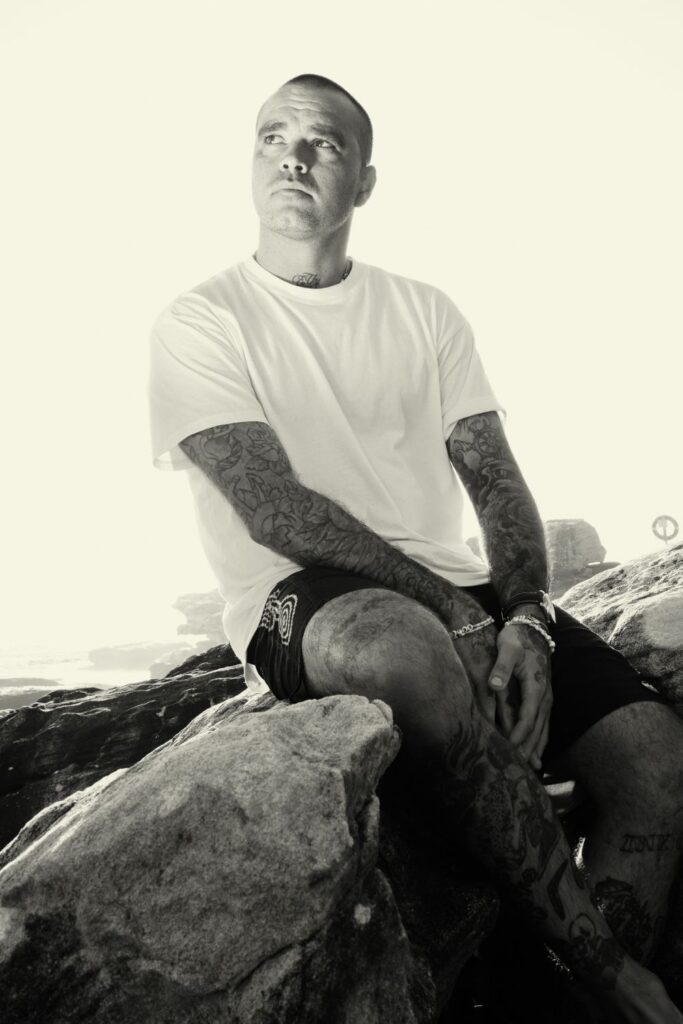

As if timing his arrival with the rhythms of nature, the pro-surfer-turned-artist Otis Hope Carey steps onto the sand just as the sun rears its head over the horizon. For most Men’s Health cover stars, a call time of half five in the morning is enough to prompt a few concerned emails from agents. Not for Carey.

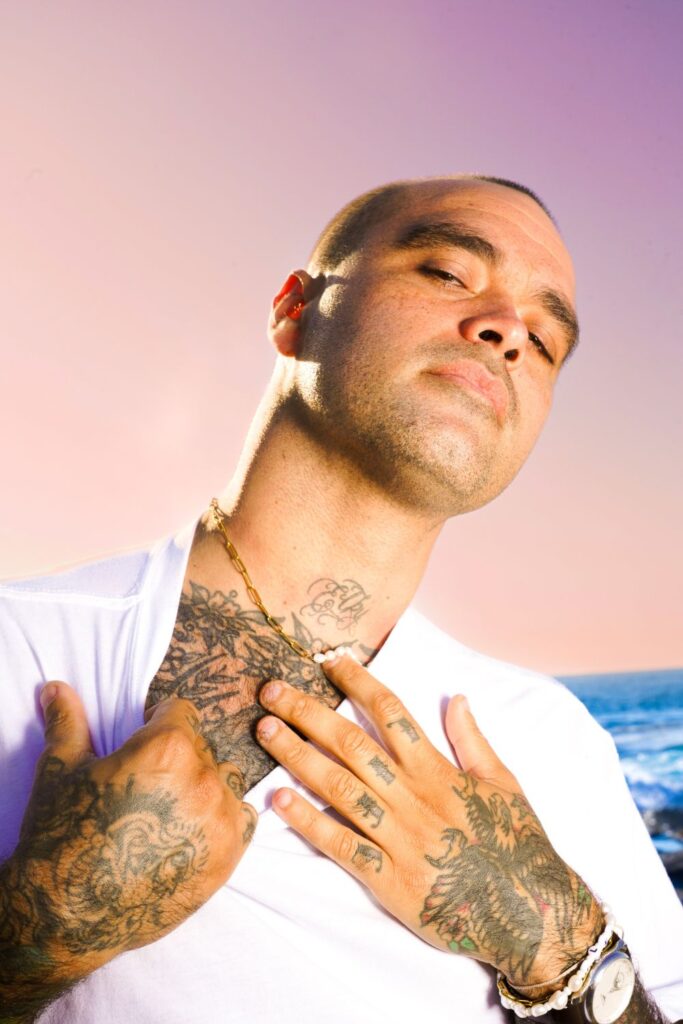

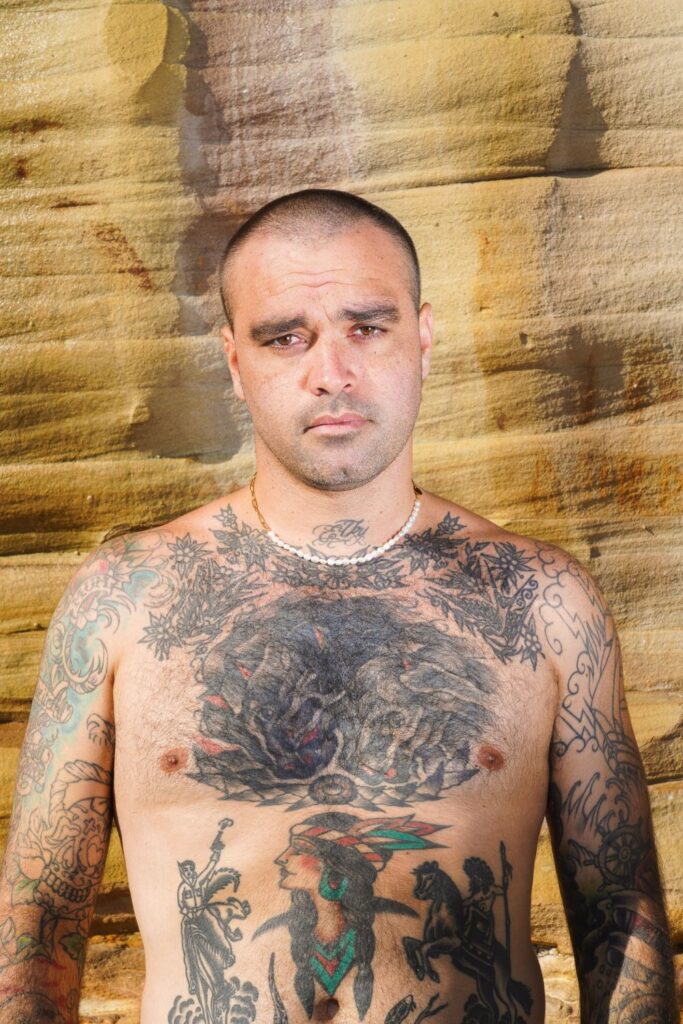

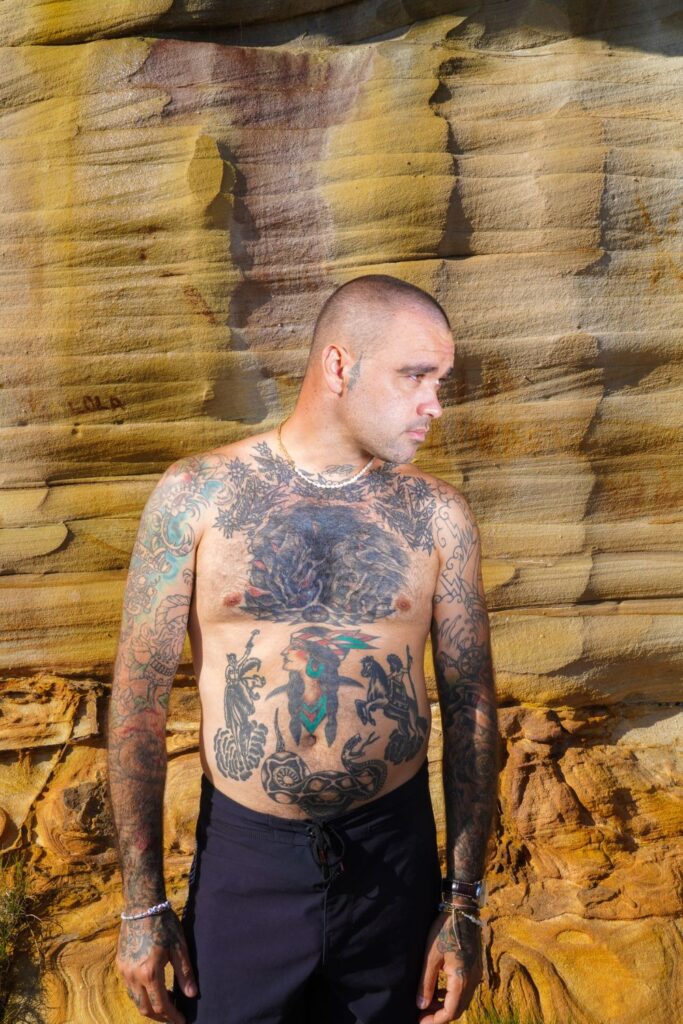

“I’m usually up at this time,” he smiles as he dumps his bag next to where our tripod is set up. “I love starting my day by the water.” In an oversized black bomber jacket, with tattoos across the side of his face and neck, Carey looks more rockstar than tortured artist. But as we come to find out, this 33-year-old is no ordinary artist: the ability to be many things at once, his is a free spirit that wriggles free as soon as you try to put him in a box.

In arguably less rockstar fashion, Carey has arrived today with his mother, Julie, in tow. And as much as we’d like to start with some small talk, the sun is wasting no time in its ascent so we politely usher Carey into position. As the click of our camera competes with the sounds of the waves nibbling at Carey’s feet, there’s a peaceful serenity to the artist that suggests a man at ease with both himself and his surroundings. This should hardly come as a surprise. For Carey, a proud Gumbaynggirr / Bundjalung man, the beach holds a special significance.

“My oldest memories are being at the beach,” he explains. “Mum had us down there when we were a couple days old. And we’re spiritually connected to the ocean because of our totem. Gaagal (the ocean) is the Gumbaynggirr clan totem. It’s very healing, very powerful and very cleansing. And I think for me, when I went through real bad bouts of depression, the ocean was always there when I needed it. It’s always waiting for you. So I was always down at the beach walking in the water or just laying in the water and talking to it. It’s a big part of why I’m still here.”

In between shots, Carey flicks away blue bottles from the water’s edge before diving in to freshen up. For a brief moment, his movements are almost seal-like as he rolls about in the waves, inviting the cold water to nourish him. He stays there in quiet contemplation for a few seconds, before returning to the sand.

***

It wasn’t until his early 20s that Carey started painting. At first, it was less about an act of creation as it was an exercise in healing; he used the craft to help deal with the depression that haunted him throughout his teenage years.

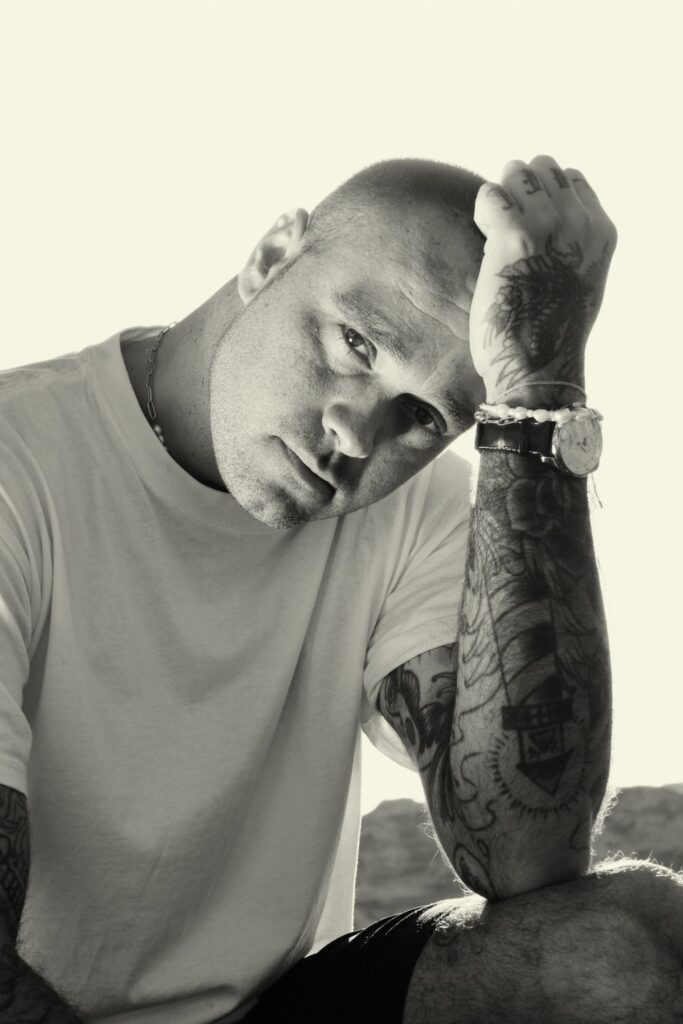

“There were some days where I didn’t know why I felt so hurt, depressed and sad,” he says. “Painting was a way of letting everything go. Letting go of the pain. When you spend a lot of time with yourself doing something like painting, you start to form a different kind of relationship with yourself.”

With each artwork, Carey found he was not only easing his spirit but developing his own unique style. Incorporating bright colours into a constellation of lines, dots and patterns, each painting by Carey is mesmerising to the eye, often inspiring new interpretations each time you revisit the piece. Both the public and the art world were quick to catch on, with Carey becoming a finalist for the 2020 Wynne Prize – a prestigious annual award presented by the Art Gallery of NSW – just six years after first picking up a brush. Fittingly entitled ‘Ngalunggirr miinggi (healing spirit)’, the painting is based on his late grandmother entering back into the ocean. It’s still the artist’s favourite piece of work to date.

For his most recent exhibition, Our Totem, Carey continues to explore the significance of the ocean and its role in the lives of his community. Exhibited at China Heights in Sydney’s Surry Hills it comprises 10 paintings as well as three sculptures made from bark that Carey sourced and treated himself on Gumbaynggirr Country. Each work features layers of lines representing the patterns of the oceans; currents and ripples intermingle to create the sensation of movement as if the paintings themselves have life beyond the canvas. There is also, like in all of Carey’s work, a rich texture that makes you want to reach out and touch them. He explains that this is an attempt to reflect the depth of each piece.

“When you have a spiritual connection to something so powerful, it’s always gonna be really layered.”

otis hope carey

Across the exhibition, lush greens give way to soft pinks and purples, suggestive of a natural world seen through a dream-like lens. Just like the morning swimmer who stares out across the ocean and gets lost in the crashing of its waves, it’s easy to immerse yourself in Our Totem, allowing yourself to be transported to Carey’s own creative reimagining of the ocean and its surroundings. The effect on the observer is profound. Sometimes art requires us to sit and marvel at the beauty of the world as if we are appreciating an inanimate object. With Carey’s work, the ocean is more than simply the muse; it becomes alive. Standing in front of the canvases of Our Totem, the ocean feels at once beautiful and powerful; a life force not simply an object for our pleasure. This perhaps gives the work a certain urgency during an era dominated by climate-change discourse. Encouraging a deeper sense of connection, Carey invites us to respect, and protect, the natural world.

Through his work, Carey says he aims to explore a “spiritual connection” to his Indigenous culture. In many ways it becomes a bridging of two worlds – the past and present, the physical and spiritual – all filtered through Carey’s own unique experience.

“We all have our own light,” he explains. “We all work out of a place that’s our truth and honesty. That’s how we all do things differently. Like for Indigenous artists, we all paint so differently to each other even though we’re all cut from pretty much the same cloth.”

“With some works I can see them; I know what they’re gonna be,” he says. “And then others, I just let it flow through me and see what happens. I don’t fight against the flow of how it’s coming out. It’s like an ethereal feeling. A lot like a feeling of weightlessness, in a way.”

To achieve this state of flow, Carey says it helps to be surrounded by family.

“There’s a lot of old people around me that support me in being able to channel that and execute it in a way that’s very true and real and honest,” he says. Though mum is quick to point out that when it comes to actually producing the work, he’s on his own.

“We just let him do his thing,” she says. “That’s why he’s here.”

It also helps that Carey moved from Sydney, where he spent over ten years, back to Coffs Harbour where he grew up. He tells Men’s Health the city started to feel stagnant. “There wasn’t enough space. I feel more free in Coffs,” he continues. “There’s more room for my spirit to breathe.”

Having spent most of his career painting out of his garage, Carey recently rented a studio a ten minute drive from his house. There’s no one else there; just Carey, a huge industrial space and his canvases. It’s here that he created all of Our Totem. Locked away for six months, the last three of which were spent working 10-14 hour days, it was a painstaking process.

“I’m always having to stretch my back and my fingers are always blistered up and sore,” he says. It’s a small price to pay, however, and Carey isn’t about to change the way he works any time soon.

“It would be easier to use stencils,” he admits. “But it makes the work less honest. It’s not flowing through you if you’re using a stale stencil that was created to reproduce work.”

“It can be really tedious at times and really tiring but then also recharging and energising,” he says of the creative process. “And I guess the reason I feel that way is because I’m channelling that connection. That’s exactly how the ocean feels at times, too. When you channel a certain energy like the ocean, you take on all the emotions of it.”

***

Carey has been in Sydney for nearly a week and it’s clear he’s itching to get back to Coffs Harbour. Back home to where his family is, where he can surf empty beach breaks with no one but his friends in the water; back to where his spirit can roam free. Home is a special place, he says, steeped in history.

“There’s a Gumgali dreaming story about a goanna and one of my favourite beaches is where the head of the goanna is. In the story, the goanna is… was it being chased?”

Mum nods.

“Yeah… he dug down into the earth to hide then popped his head up and his head is the rock. It’s a really different rock, too, it’s square and flat so it sticks out of the environment. It’s nice to be able to know the history in that light and look at your country through storytelling.”

It’s this relationship with the natural world that underpins much of Carey’s life both in and out of the studio. When he’s fishing, Carey says he relies on his understanding of the landscape to know when to go out and what species will be there.

“Sometimes you gotta look at the trees and plants and when they flower,” he explains. “There’s a yellow flower I know of, I don’t know the name, but when it flowers, the freshwater turtles would start laying their eggs. And so then back in the day, you’d know once they lay their eggs, you can then go and catch ’em and eat them.”

“There’s only certain times of year when it’s plentiful though,” adds mum.

When Carey’s not fishing or locked away preparing for an exhibition, you’ll more than likely find him on the beach. Because, while painting is his career and passion, Carey’s first love will always be surfing. After a challenging school life, it was time on his board that kept him grounded. His talent eventually took him onto the pro tour where, in his early 20s, he was being paid to travel and surf the best breaks in the world. On paper, it was a dream come true, but something wasn’t right.

“I enjoyed the surfing aspect of it,” he says. “Just not competing against others. I used to love travelling, but as soon as I’d have to go out for a heat, I’d just be a bit deflated.

“I feel like surfing’s more of like a way of life,” he continues. “As soon as you put it into that competitive environment, you lose a bit of that connection.”

Just like with his art, Carey’s surfing is a way to foster a deeper spiritual connection to his culture. “It helps you connect back to yourself,” he explains, “which connects you back to your culture.” It’s a relationship that can’t be translated into heats and titles; more about the feeling than the outcome. With a board under his feet, Carey looks at ease, working with the ocean rather than against it, he carves smooth lines into the wave just as he does on canvas. It’s effortless. Whereas some surfers muscle their way into position, Carey lets the wave come to him, allowing the rhythms of the water to flow through him.

Since Our Totem wrapped, he’s been in the water as much as possible. Sometimes in his lunch break with his brother, other times before he hits the studio.

“Sometimes I’ll just go surfing all day,” he admits, smiling.

Carey’s decided to take a short break from art to focus on his surfing. He wants to spend more time with his three kids and more time in the water.

“Next year is about more family and more surfing,” he says. “I’m 33. I’m not gonna be young forever, so I wanna do as much surfing as I can and create good surf content while I’m young. Painting’s always gonna be there, but surfing’s not.”

After this shoot wraps, Carey will travel to the city to finish a mural he was commissioned to do for a high-end hotel. On the agenda for this week is also a trip to Byron to see ‘Chris’, which to us laymen is Hollywood superstar Chris Hemsworth. A huge fan of Carey’s work, the actor has commissioned a number of pieces from Carey and even asked him to design the cloak he wore in the opening scene of Thor: Love and Thunder.

Most recently, Carey shot an episode for Hemsworth’s new show Limitless, where he took the actor on a four-day trek through Gumbaynggirr country alongside the Dunghutti and Anaiwan people, discussing and learning about Indigenous customs. It was an opportunity Carey relished. A TV show on Disney+ may seem a world away from an art exhibition in Surry Hills, but in many ways, the result is the same: a deeper connection to culture, to the land – maybe even to one another.

“I’ll probably spend a few days in Byron hanging out with Chris,” says Carey, as if that’s a totally normal thing to drop into conversation. From there, it’s straight to Coffs Harbour. He’ll dump his stuff then make the short trip to his favourite beach. He’ll take out his board and jump into the ocean – back home.