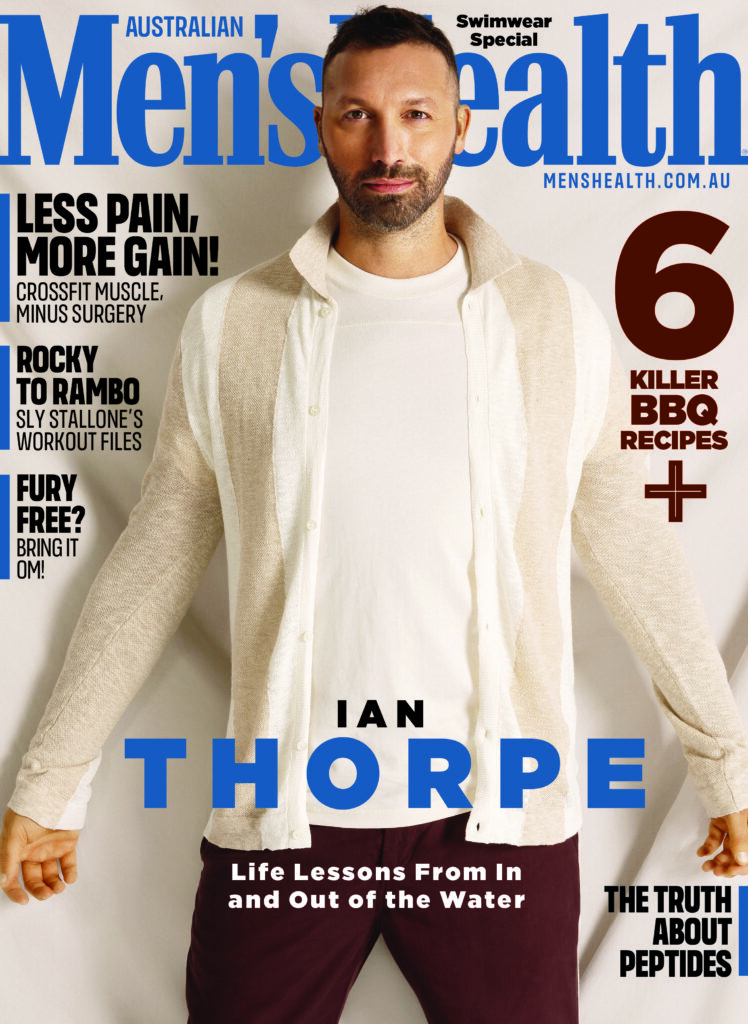

The tall man who arrives bang on time for the Men’s Health photo shoot is unmistakably Ian Thorpe: recently 40, he’s changed little since his days of gliding up and down the pools of the world as though born to the water. There is something different about him today, however, apart from the beard. It might be a hint of nervousness he seldom betrayed at his competitive peak.

Since his mid-teens, he’s been snapped a million times. Yet today he seems faintly ill at ease in front of the lens and wants no part of appraising the images that appear on the monitor. Perhaps he’s a touch insecure; perhaps he doesn’t care enough to fuss; or perhaps he wants simply to get on with things. Regardless, he’s cordial and professional, prepared to strike poses but nothing extravagant; prepared to smile but only occasionally.

It’s later, while talking, while looking back on his life and especially his swimming days, that Thorpe comes to life. For all its associated pressures and controversies, he reflects on that heady time with a palpable fondness. And surely with pride, as well, for what a time it was. What a magnificent, glorious show Thorpe put on for the rest of us.

Let’s start with the numbers game. At the 2000 and 2004 Olympics combined, Thorpe won five gold medals across four events, the equal-most by any Australian in history (that tally having been matched in Tokyo last year by Emma McKeon). Between 1998 and 2004, he claimed a further 11 gold medals at world championships. World records? He set some 23 of those.

But Ian Thorpe – the Thorpedo – was so much more than an amasser of prizes. In his prime – which began when he was a floppy-haired 15-year-old from Sydney’s southern suburbs – he exuded the quality of invincibility reserved for the chosen few. To see him on the blocks was to know he would win. In his pet event, the 400m freestyle, he beat all-comers for six years at every big meet, swimming in a way best summed up by fellow Olympic champion Duncan Armstrong: “He caresses the water, but when it’s time to be brutal he’s like a raging bull”.

For me, the race that defined Thorpe was not an individual event but a relay – the 4x100m freestyle on the first night of Sydney 2000. You know what happened, right? On the last lap, Thorpe, a middle-distance specialist, trailed the American hotshot Gary Hall Jr, a pure and lethal sprinter, yet overhauled him to win by a hand-length. It shouldn’t have been possible. Shouldn’t have happened. But that was Thorpe.

What made him so great? Supreme technical efficiency? Enviable physical strength? Cartoonish elasticity? A long frame and colossal feet? An iron will? Nerves of steel? All those things applied. But athletically speaking, completeness was his outstanding trait. Thorpe had it all.

Out of the pool, he charmed everyone with his maturity and decency. People saw in him, observed his late biographer, Greg Hunter, “a kind of instinctive understanding of what it is we’re all supposed to be doing in this life. There is in the collective unconscious the idea that some among us are old souls – people who seem to have been here before, people who have such an understanding of things that they can see the big picture before the rest of us, and act accordingly. It’s not just a matter of intelligence… it’s more about wisdom, aligned with moral courage.”

Thorpe retired from swimming in 2006 aged 24, before making a comeback five years later when the magic had faded. Since then, we’ve heard him on TV as a commentator and seen the reports on the various ups and downs in his life, one that’s been inevitably complicated by the void of post-sporting greatness, challenges arising from his sexuality (Thorpe came out as gay in 2014), and the sadness and cynicism which settles on the highly intelligent whenever they look too closely at a flawed world.

What role does swimming play in your life nowadays?

Ian Thorpe: Well, I don’t swim. I had shoulder-replacement surgery [in 2015], so I can’t really swim. I can do enough to catch a wave, but not a lap in the pool. I knew before the surgery that would be the case. Looking back, I think I romanticised what swimming was and is.

How so?

I forgot about all the freezing-cold mornings and being in agony after sessions. Look, I can still meditate in the pool if I feel like it, but repetition is where the beauty comes from in swimming.

Minus swimming, then, how do you train nowadays?

IT I go to the gym two or three times a week for weights, and some of that is rehabilitation [and prehab] work. I do that with a physio who happens to be a bodybuilder.

Do you still feel connected to the Ian Thorpe who competed on the world stage?

No. It’s more like I train for a healthy lifestyle. The only cardio Ido now is walking, at a pretty quick pace, just to reach the right heart rate for me. And I don’t listen to music when I walk.

Really?

Yeah. Everyone thinks it’s a bit odd. For me, music’s a distraction from being mindful. When I’m walking, I’ll try to notice something that’s different. I’ll be like, “Oh wow, these apartments have water views – I wouldn’t have known”. And then, “Oh, I should have worked that out because the cars are parked out the front – that makes sense”. When you’re walking, always look a little further ahead than you think you should. That’ll get your posture right, as well.

What does your diet look like these days? Are you fastidious?

I have to be. It’s too easy to gain weight otherwise. I’ll compromise on portion sizes sometimes with meals that I really enjoy eating but aren’t all that healthy. But I still get to enjoy things. When I go out for dinner, which is probably twice a week, I’ll eat what I want except… unless it’s your favourite dessert in the world – a panna cotta, say – it’s not worth eating for me. [Snacking], I’m the kind of person who’ll eat mixed nuts and seeds if I feel I’m losing my energy. I’ll go to that rather than something sweet. I also use supplements, like Anthogenol [anthogenol.com.au] and magnesium and calcium for recovery if I’ve had a big session.

“It’s having talent and then working extremely hard. Just because no one has accomplished something before doesn’t mean you can’t do it”

Do you have any habits aimed at managing your mental health?

That’s part of the walking thing for me. That’s my time to freshen up. And I know if I’m struggling a little bit with my mental health – because it fluctuates – you try to find that motivation to get outside and go for a walk. Because it starts to clear your mind a little bit. People would know from lockdown that being stuck in a house is not good for you. I regularly see an expert as well, probably quarterly. I look at it as outsourcing any problems.

Like seeing a trainer?

Well, it is. You see an expert in every other field, so I see an expert in this field. And a lot of it is, again, preventative – just checking where I’m at and how I’m going. For me, it’s also a bit of a safety net. We usually speak to them when we’re at a crisis point… when it’s gotten to a point where you really need them.

You’re turning 40 in October. [Thorpe turned 40 on October 13, after he did this interview.] How are you feeling about that?

I think it’s the first proper birthday. The first, yeah, real birthday. I’d prefer if I wasn’t [laughs]. I’d prefer to be turning 30. But I’m actually okay with it. Most people are surprised that I’m turning 40. They assume I’m either older or much younger. It’s one or the other. And I’m actually starting to judge myself a little bit on the

40 thing. So, if I come up with something spontaneous, I think, Is this because I’m turning 40? Is that why I’m thinking like this?

A potential mid-life crisis?

Yeah. So, I did a show – I did This Is Your Life – and I was like, I’m not halfway through my life. Why are we doing this now?

What was that like, reviewing your life in that format?

It was odd, because I would’ve rather have spent the time with my friends and the people who appeared and had someone else [as the focus]. That would’ve been my preference. But the following day, I caught up with all of the swimming guys – which was cool. We don’t get to see each other all that often. Not often enough.

Looking back on your swimming career, what qualities made you so good?

It was a combination. If you listen to a physiologist, they’ll tell you it’s to do with your heart rate or the composition of your body. If you listen to a physio, it’ll be about your flexibility and your ability to rotate. If you speak to a psychologist or psychiatrist, they’ll say it’s your mental strength. What I say is, it’s none of those but the combination of all of them. And it’s also having talent and then working extremely hard at that talent while not setting a limit on what you can accomplish. Because if you say, I want to win a gold medal, you’ve already limited yourself. And just because no one has accomplished something before doesn’t mean that you can’t do it. What I’ve seen in sport is there’ll be someone – the pioneer – who’s able break through a brick wall that no one thought could be smashed. And then a decade or two later, everyone’s swimming at that level. Everyone’s caught up and then we’re waiting for the next person to break through. It’s also having, I think, a childlike mentality. I think that helps.

Anything’s possible?

Anything. And you really have to believe that. And I tell people that goals are something that you can set out to accomplish. If you work hard at it day in, day out, you will get there. But if you keep on getting there, you’re setting your goals too low. The dream… that’s the loftier ambition. That’s the thing you’re a little ashamed to say out loud. It’s like being a kid and saying, “I want to be an astronaut!” Now that’s a dream and that’s how it should feel. In sport, having the innocence of a child in how you perceive the world is definitely advantageous. But then what happens – and this is part of growing up – people start to plant seeds of doubt in your mind. It doesn’t hit you straight away, but this doubt starts to build up. I was told by a coach at the Sydney Olympics, “If you can conserve energy in this first race [the 400m freestyle] for the [4×100] relay… you should think about that”. And everyone’s like, Okay, so you don’t even have to try to your fullest. Which was pretty messed up, I have to say.

What was your parents’ contribution to producing a champion?

So, we had a rule. My sister [Christina] used to swim a bit as well, and the rule was we had to wake up our parents [to take us to practice and meets]. So, you would set your own alarm and wake them. Another rule: no matter what sport we were doing as kids, we had to commit to a season. So, if I said, “I want to play soccer this year”, it was like, “Great, you can do soccer – it’s through to the end of the season”. It was the same with swimming. And at the end of each season, we had a break from our sport before working out if we wanted to do it again. My parents [Ken and Margaret] are quiet. They’re humble people. So as for my accomplishments, whether at school or in the pool, they were never overplayed to me. My parents are the opposite of typical ‘tennis parents’ – or ‘swimming parents’ for that matter. And that helped.

“When it came to retiring, it had nothing to do with swimming. I could not handle the amount of attention that was on me.”

Was there a pivotal moment in the juniors when you knew swimming was something you were going to pursue and conquer?

IT The only thing I can think of, I can remember hearing my father telling one of his friends how good I was. He would never say that in front of me. I’d never hear that. So, when I heard him speaking to his friend, I was, Oh, okay – I’m really good at this. But I always thought I might be a child prodigy who’d never make it at the elite level – which is something I’ve seen happen so many times.

What was your most exhilarating moment in swimming?

Look, if I could pick a night, it’s the 400 and then the 4×100 relay in Sydney. And then, if I look at Athens [2004], it’s the 200m freestyle there, and defending my 400m Olympic title was nerve-wracking for me. I was swimming that race with a lot of emotion, which is not a good way to swim a race. And then there’s some [races] that people haven’t seen. Like, some of the things that have been most exciting for me, it was only my squad and my coach who saw them. No one else.

Do you still find yourself reliving moments or rivalries?

Not really. It’s only when people bring stuff up, like when I’m doing a speech somewhere in the world and the organisers will show clips. I just won an award in Italy, and they played all my Olympic wins. And it was funny because I’d never seen footage with Italian commentary before. And when I watch those old races, I usually end up smiling because I’m still correcting things. I’m still, Hmmm, that could have been better.

What was the most challenging part of professional swimming – training, travel, injuries, stress?

Let’s go with stress because there are certain things that you can change and certain things you can’t. For me, when it came to retiring, it had nothing to do with swimming whatsoever. I had got to a point where I could not handle the amount of attention that was on me and some of the circumstances. No one can teach you what it’s like to have stalkers. Knowing that when I walked into a pool, I needed proper security, that there was a direct and indirect threat against your life at that event. I never thought of this when I was young – being followed by paparazzi… all of that. People having an opinion on my life. The context of swimming had become entirely different to what it was when I was a kid looking at the sport with wide eyes.

You’ve alluded to your retirement, in 2006. Do you think, in hindsight, you may have retired prematurely?

No. I had to. Even after the Sydney Olympics, I wasn’t sure that I wanted to do another Olympics. I’d achieved my dreams. It was, Do I just move on? I’m a 17-year-old – do I move on with my life now? That was what I was thinking for a little while. But it changed. I was, No, I’m not done yet.

All athletes who achieve success must deal with The Void. And generally, the greater the success, the deeper the void. Tell us about your transition from swimming champion to not-so-ordinary citizen.

IT So, I work with a youth mental health service called ReachOut, and I chair the AIS Athlete Wellbeing Advisory Committee, and these days we know a lot more about athletes than we used to. We prepare people to perform [but] we often don’t prepare them to succeed. I was reading a study around [retired] English Premier League players. They’d been so connected to one world their whole lives that they’d disconnected from their families. They had something [their sport] that defined them as people and then that disappears. They don’t have the adulation anymore, so it’s almost like you go through a process of mourning. And I don’t say that lightly. Something elite athletes should be doing is what we call ‘de-training’… it’s starting to prepare for life as though you’re about to stop your sport, adjusting to what your routine will be post career. That’s something that we’re doing with the AIS. We’re looking at athletes pre, during and post, and if we get the pre part right, we’re hoping the transition out will be a lot easier.

But how do you identify when to start training for post?

IT We think from the beginning because the reality of sport is that your career can be over at any moment. You can have an injury and that’s it. You have to prepare for Plan B. People say, “Plan B? Shouldn’t they just be focusing on sport?” But that’s a very simplistic way of looking at sport and quite antiquated, really. We find that athletes have more success when they have a balance to their lives, when your self-worth isn’t based solely on sport. It’s kind of like a stool. If you sit on a stool and you think there are four legs on it, you can sit on it for a very long time.

You take away one leg and it will start to wobble, but you can still kind of sit on it. If there are two legs, you’re going to struggle. And with one, it’s impossible. A life built on one thing is precarious. You’re headed for a fall.

And what makes up the legs of the stool you’re plonked on these days?

For me, it’s work. It’s hobbies. It’s relationships. And then it’s giving back, which is the philanthropy work that I do. There’s exercise in there as well. I have five [legs].

That’s a sturdy stool. What are those hobbies? What gets you out of bed excited?

I like sailing. I wanted a sport I could do for the rest of my life. Creative pursuits as well: I love working on brands and helping people out to start off brands on an entrepreneurial level. I’m a bit of a US politics nerd, as well.

Looking back on the past 40 years, what was the happiest period in your life?

I think when I was a kid and when I first started [swimming], because I started travelling when I was 12. So, my world went like this [stretches his arms wide] very, very early. And so, that was my education: I was studying on planes and then also experiencing what the world is like. And that has shaped my perspective on what you can do. The experiences that I’ve had are… well, they’re extraordinary. They’re not normal kinds of things and so they shaped me. And then, after coming out, after being out for about a year, it was like when I first got my license. You felt that amazing sense of freedom!

Like looking at everything with fresh eyes?

Yeah. Even though everything is familiar, there’s something different about all of it.

Why was your 2014 interview with Michael Parkinson the right time for you to come out as gay?

Look, I don’t know if there’s… I think it’s different for everyone. But I first came out to my family. Actually, no, I came out to a couple of my friends first, and then I told my sister. And then I was going to tell my mum and then I was going to tell my father. That was kind of the order that I’d worked out in my head. And my sister said to me, “Whatever you do, don’t tell Mum before you tell Dad”. I was like, Shit! I thought, I’ll have to tell them together. So, I sat them down and told them. That interview was something I knew I had to do, and I thought, I’ve already told the people I care most about; now I may as well tell the world. I rang my agent and said to him, “Look, I’m gay, and I want to say this in the Parkinson interview”. And he goes, “Okay”. My parents said to me, “Do you want to get used to it before you come out to the world?” And I was, “I’ve been in the closet for so long now, I’m not taking a step back in”.

When you agreed to that interview, coming out wasn’t part of the plan?

No. So, I spent some time with Parky’s family near where he lives. And about two days before the interview, I told him that he should ask me if I’m gay. And he went, “Okay”. And I said, “Because I will tell you that I am”. And he goes, “Okay, thanks for telling me”. So, he then had to work out how he was going to approach that, which couldn’t have been easy, and I thought he managed to do it in a really thoughtful and sensitive way.

How far do you think we’ve come as a society since then in terms of the acceptance of human differences?

Well, that depends on how you look at this. We’re getting better. It’s around 70 per cent of people who support marriage equality. If we look back to 2004 – for me, the time of the Athens Olympics – that number was just under 35 per cent. So, it’s doubled since then, but then there are also some scary stats out there [in terms of what people think should happen to gay people]. And when I look at the youth-suicide statistics… how many more people in the LGBTIQ community [have taken their own lives] and how many more are susceptible to taking their own lives. We haven’t done enough there. What the marriage-equality [vote] did… it was a starting point for conversations about what can happen [to improve society]. In schools, for example – what should be taught is that marriage is between two adults, two consenting adults. This is what the Australian government now recognises. We know with young people, the first place they go [with questions and concerns about sexuality] is their family and friends – which is great. The next place is the internet, so the internet needs to be well resourced. And this relates to part of the work I do with ReachOut.

Do you think it would’ve been easier for you to come out in today’s environment?

Absolutely. See, I got asked by a journalist if I was gay when I was 16. That would never happen now. But this journalist was told that their job was on the line – or that was my understanding, anyway. And it would be the exact opposite right now – you would lose your job if you did the same thing today. Also, back then, the language around this issue… it was said I was being accused of being gay. So, you’re thinking about this in a negative sense. You never thought there was a great side to being who you are. You want to hide something away. And when I was talking to you about the pressure that I was under and how I stopped competing because I couldn’t manage that… this was another thing I had to manage. That’s how I felt, and I didn’t think that I was ready to add this on top. I was also thinking at the time, How much does it actually matter? How much does my sexuality affect me as a human being? Is it the thing that defines me? I don’t think it is. So, I didn’t realise how important it was for me to find my authentic self. You realise all this in hindsight. But when I look back on my career, we’d have training camps in places where it was illegal to be gay, so if I’d have come out earlier, I may not have been able to train with the rest of the team or compete at certain places. I’d probably have been booed as well. And as a young person, that’s not what you want. I wanted to fit in with my peers and even around the celebrity side of what I did. I just wanted to be part of the group. I didn’t want to be the one sticking out.

What do you imagine your future to be?

That’s a huge question. Look, I’ve learned with life that there are destination points that you want to get to – they can be specific – but the way you get there is not a straight path. And some of the best adventures and times of life happen while you’re getting sidetracked along the way. My goals are less short term and more medium and long term. It’s being able to look back and see a collective piece of work that I’m interested in. When I’m 70 or 80, that’s the time I want to be able to reflect and say it was a very full life. And the reason I’m a little bit lofty and a little ambiguous with this is that I never expected my life to be how it is right now. It’s kind of quite bizarre. I happen to be a successful athlete who has then had these experiences in the world that few people get to have and not many athletes get to have. The fact I’m asked by people, “Do you want to go into politics?”, or, “Do you want to turn up and model eight different outfits today?” And the invitations that I receive and the people I meet who are the very best in their professions inspire me. I had a career that was quite rigid, and I love the structure that it had, but I’ve realised that isn’t what I want for the rest of my life. I look at everything now and I like to have fingers in many pies. A week ago, I just finished a commentary stint; now I’m shooting for a magazine; and after this I’m going to a charity board meeting. So, it’s all mixed up. None of my two weeks look similar at all.

Is there anything specific you still want to achieve?

Yeah, there is. You know what? I want to live life like I did when I was a kid. I want to have that feeling in my life that I get excited by what I do and feel like everything is… just limitless in what I can do. So, in terms of what I do with my business interests, how do you create success there? People would go, “Well, it’s to make a certain amount of money”. But that isn’t what motivates me. So the question becomes, what does? Reshaping how business operates might be something… how it engages with the consumer. And what it does in the social space – social responsibility. That part is more interesting for me. The other thing is finding the right person to settle down with. I don’t know if that’s supposed to be a goal or not, but it’s something that I would be happy with because at times it feels as though it’s the only thing that’s missing from my life that I’d like to have. And most of the things that I would like to have, I usually have.