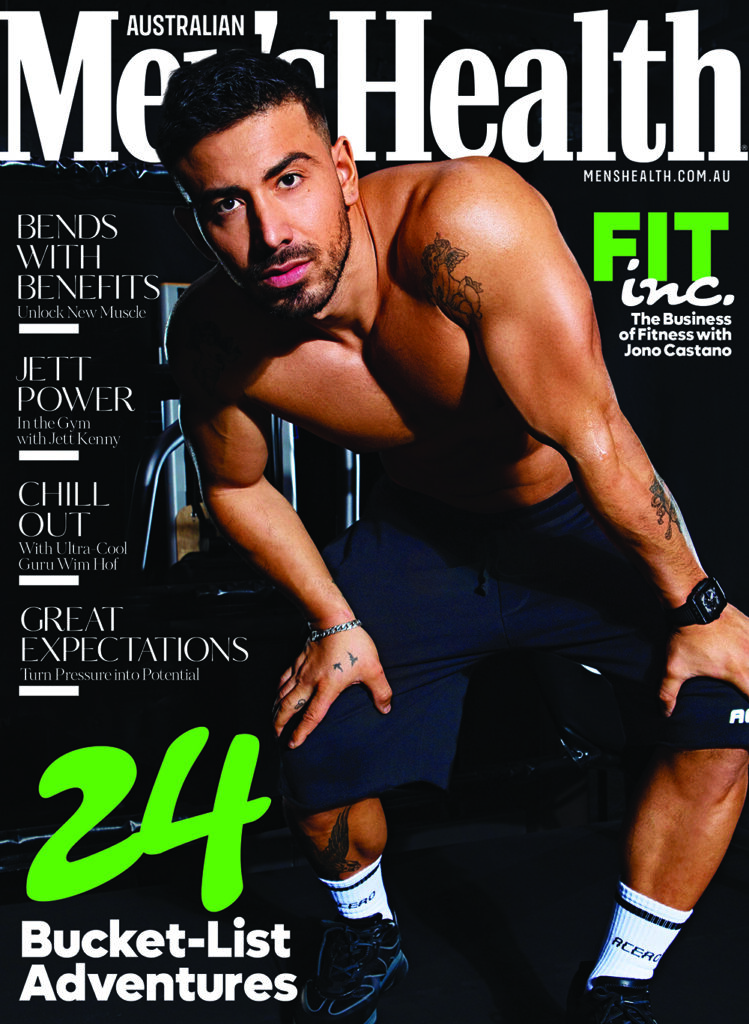

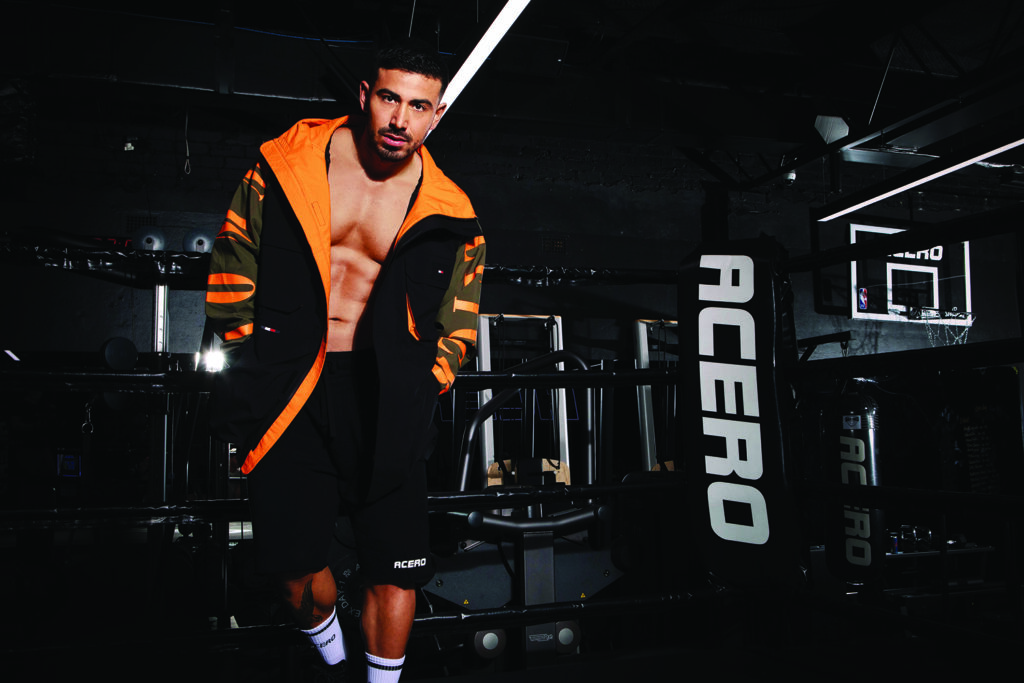

Jono Castano’s gym, Acero, looms wholly unassuming on Anzac Parade in Sydney’s east. Past graffitied facades and buildings decorated with posters so haphazardly pasted on their peeling edges threaten to be lost entirely to the wind, a single black sign with white lettering marks the gym’s entrance.

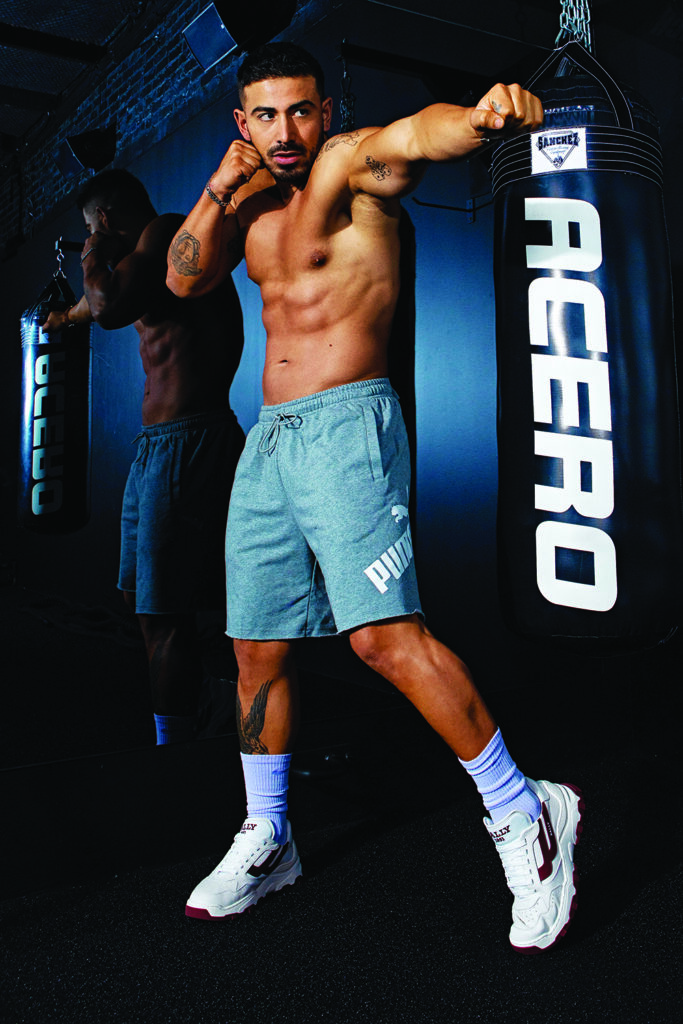

Pedestrian traffic is lost as you climb the narrow staircase, drowned out by a soundtrack of certified club bangers: Drake, Snoop Dogg, Jay-Z. All on heavy rotation.

Inside, the gym floor is far bigger than a cursory stalk of its Instagram would have you believe. With an all-black colour scheme that incorporates both the walls and gym equipment, Acero boasts the kind of premium allure you’d expect of the velvet rope section at an all-hours party; one where admission is reserved for close acquaintances and Hollywood stars. As it turns out, at Acero, all who enter are treated as VIPs. There’s a palpable energy, an infectious enthusiasm you feel from the instant greetings uttered by trainers and faces that look up, mid-hip-thrust or squat. Regardless of the weight resting precariously on their shoulders, a salute in the solidarity of physical suffering is always forthcoming.

Of all the greetings, it’s that of Castano that’s warmest. He emerges from the trainer’s staffroom wearing casual sweatpants and a sweatshirt branded with the gym’s logo. Sensing his presence, those working out squat a little lower, punch a little harder, grunt that much deeper. They know Castano’s attentive eyes are all-seeing. But they also recognise that this is a man who created an empire and to step foot inside is to live by a simple doctrine: give nothing short of your best, daily.

Castano is revered within the fitness industry. Though he once charged $40 per 45-minute session, his rate has now climbed upwards of $180, with clients travelling interstate just for a chunk of his time and expertise. Even so, Castano seems oblivious to the reputation that precedes him. He breathes life into a room not by way of extravagance or brash conversation, but in his disarming cordiality. He extends a handshake, is quick to offer a coffee and proceeds to show me around this space he is clearly proud of; a space that has, in recent months, allowed him to process complex emotions and personal turmoil, all to find himself again. As Castano will tell you, it’s a space that reignited the passion that was so pivotal in his rise to the top of the fitness industry.

When Castano takes out his phone to show me photos of what preceded Acero – a decrepit boxing gym where industrial lighting hung from naked wires – it’s hard to believe it’s the same place. If you know anything about Castano, though, you know that his is a life devoted to transformation, even if he’s known more for startling fat loss and revamped body composition than slick interior decorating.

With some 820,000-and-counting followers to his name on Insta and a stable of acolytes that include the likes of Rebel Wilson, Michael Clarke and Sir Richard Branson, Castano is a magnet for commercial partners – he’s an ambassador for Hublot Watches and Melrose Health and a member of the SmileDirectClub Confidence Council. While it might be easy to reduce the 31-year-old’s success to luck, to do so would ignore the fact that at a time when society seems beholden to the quest of perfection, Castano steers solely towards authenticity. “You can see straight through that perfection these days. A lot of people aren’t who they present on their social media,” Castano sighs. “Even clients, they don’t want a person that just counts reps. They want someone relatable, that they can talk to.”

Castano shares a lot of his life with his followers. His incredible work ethic and dedication to his craft make him someone who is readily accessible. Clients know that he’s only ever a text or phone call away, all too ready to impart wisdom that will help them through any mental or physical hurdle. It’s this point of difference that has seen Castano become one of Australia’s most sought-after trainers, known for his 12-week transformations that have the power to break the Internet. But as he recently learned, there are times when one runs up against the limits of hard work. For Castano, that moment arrived last year, after a divorce drained him of his passion, leaving him searching for answers and a sense of identity.

JUST FOR KICKS

Before Jono Castano came to master the SkiErg, he cared only for a soft touch and quick footwork. Growing up in Pereira, a small town located a two-hour bus ride from Bogota, Colombia, his days revolved around football. Venturing outdoors with a ball glued to his feet, he joined a group of neighbourhood kids for hours of friendly competition played along dirt roads, empty streets and abandoned football fields. As the most popular sport in the region, football represented a way out for those willing to hone their skills.

Even at young age, Castano sensed the possibilities professional sport might offer him and set about becoming the best player he could be. He began training twice daily, sacrificing the frivolities of youth as indulgences like sleep-ins and a sweet tooth were steamrolled by discipline and drive. Ask Castano if he found it difficult, at such a tender age, to give so much of himself to a sport that demands everything yet rewards so spraringly and he’ll waste no time deliberating. With a shrug of his shoulders, he explains: “Soccer was my whole life. I knew nothing else.”

Long before Castano started playing football professionally, it was his dad who found a way out of Colombia. In 1997, his father migrated to Australia alone, arriving with no English, nor connections that would allow him to utilise his professional skillset. He took jobs in cleaning and construction, the kind where payment never adequately reflects the labour-intensive demands. Thinking of the young family he’d left back home in Colombia, he worked tirelessly to save enough money to fly them over, hoping to offer his two sons opportunities and a lifestyle that had eluded them in Pereira. Castano was six when he came to call Fairfield West, in Sydney’s western suburbs, home. He may have been too young to fully comprehend the sacrifices made by his father back then, but it’s those actions that he credits for shaping the man he is today. “He just worked his ass off to fly us over here to give us a better future,” he says. “If we stayed there, who knows what life would have been? I have no idea to this day. I can just thank both my parents for the opportunity they’ve given us.”

HARD GRAFT

Here on Australian soil, Jono Castano doubled-down on his footballing aspirations. He began travelling for the sport at just 16 years old, returning to Colombia to play before going on to represent teams in Singapore, Indonesia and Belgium. “When you think about now, I’m so self-sufficient and independent because I was pushed away from my family at such a young age,” Castano says. “Family has always been on the back-burner because of that. I’ve always just wanted to focus on my career.” It’s the kind of trajectory that has all the makings of a Disney movie, but Castano is quick to admit that the mental and emotional struggles he experienced during this period clouded any perceptions of early success. He suffered from homesickness, faced criticism from coaches and fans alike and dealt with constant uncertainty regarding his playing career. When he turned 24, Castano decided to hang up the boots for good.

At an age where friends were steadily climbing the corporate ladder and ticking off career objectives like items on a grocery list, Castano decided to start on a new path. After earning his training credentials, he landed a job as a personal trainer at AnyTime Fitness, before moving onto Virgin Active. He admits to being immediately taken by the profession. He loved the reciprocal trust that exists between a trainer and client, the fact that each person he worked with was a unique individual with their own goals, injury history and challenges. He loved that his expertise could produce physical results his clients had never seen before. But perhaps most importantly, he loved that he could elicit mental and emotional breakthroughs, too. That he wasn’t simply getting someone into shape, but changing their life in the process.

“I never miss someone’s session, no matter what. I’m always going to be there”

In the highly competitive corporate gym sector, Castano employed the same tireless work ethic he’d once devoted to football. Every hour he could, he’d be in the gym and when not working with clients or devising a comprehensive program, he’d stand chatting with guests as they entered reception. Those conversations saw Castano amass a workload of 70 sessions a week, often knocking out fifteen 45-minute sessions a day. “It was an early start and late finishes, a lot of repetition,” says Castano. “But that helped me perfect my craft and work with different personalities. I always tell any new trainer that you have to be prepared to work hard if you want to stay in this industry for a long time. People ask me, ‘Hey Jono, how did you get to this point where you have your own gym and built your own following? How did you do all that?’ It’s just consistency, repetition, on the daily.”

For those on the outside, Castano’s rise to the upper echelons of the fitness industry may seem like an overnight success story. Such a perspective fails to acknowledge the long and constant grind. Priding himself on not missing a session with a client for months on end, Castano realised not only his passion for the craft, but his point of difference. Surrounded by trainers who cared only for the financial rewards associated with signing a client, Castano was only ever dependable. Even now, as we sit chatting in the staffroom at Acero, his phone lights up like a pinball machine, a bombardment of likes, messages and notifications dazzling the screen. I struggle to tear my gaze away from the tempting glow it emits from the coffee table, but Castano’s never deviates from my own.

This, his clients already know. The man is always present, considerate, focused. To be in his presence is to receive his full and undivided attention. Call it the Castano Effect: you soon learn that in a world where we are each fighting to maintain one another’s attention, Castano holds your own with ease. “When you have the skillset to open someone up and get deeper information from them, that’s where trust is built,” he explains. “I think growing up I learned to be a good listener. It’s those small skillsets you learn throughout your life and that’s what made me different. You can never get time back. I never miss someone’s session, no matter what. I’m never going to call up or text someone. That’s the key thing with my business: I’m always going to be there.”

NO FILTER

If personal training is a business focused solely on one’s individual expertise, Jono Castano is his own best advertisement. His is the kind of gym-honed physique you’d expect of a Hollywood star making their Marvel superhero debut, except in this instance Castano doesn’t care for blow-outs in post-production. The washboard abs and bulging biceps are simply a product of his work ethic.

In a hyperconnected world in which social media seemingly dictates both conversation and the news cycle, most of us don’t bat an eyelid when scrolling past a gym selfie and flexed muscles. But when Castano was finding his footing in the industry, his propensity for posting raised eyebrows and saw him cop a stern warning from superiors. A conspiratorial smile stretches across his face as he recalls a meeting with his bosses at Virgin Active after creating his Instagram account, one in which they asked Castano to “pull back” on the posting. As he tells me, “It was nothing bad, I just don’t take life too seriously. I used to get teased about it all the time but I just kept going with it.”

Back then, the world of personal training was largely represented by two titans of the game, Michelle Bridges and Shannan Ponton of The Biggest Loser. It wasn’t that it was a new phenomenon, but there wasn’t yet the demand for applied training skills there is now.

“I was here at the gym surrounded by amazing people… having that support is the perfect way to find yourself again”

According to reports from industry and market research database firm, IBISWorld, the market size of personal training here in Australia is now valued at $483 million, reflecting an industry that has become increasingly competitive. It’s remarkable, then, that Castano was able to cut through the noise social media generates. He might be his own best advertisement, but his followers understand that he’s never selling anything except his most authentic self. His following is one that was built simply by documenting his own training and daily routine.

Still rubbing sleep from his eyes as he filmed early morning starts, followers watched as he worked with clients of all demographics and fitness backgrounds and still managed to deliver results.

Free of perfected edits, his posts were all grit, no gloss; a raw and unfiltered communication stream delivered one-to-one. It felt personal. Interspersed between the training tips and gym selfies were holiday snaps, a relationship hard launch, daily musings and family celebrations. It all served to present Castano as a multi-dimensional human being, far removed from the ‘machine’ and ‘gym rat’ labels he was often saddled with. Castano was simply a driven individual with a desire to test his limits. He made mistakes, experienced monumental highs and personal lows, but always returned to the bedrock of that early morning gym workout, knowing it was this that made him a better partner, a better trainer and a better person in the process. He was, by all appearances, just like the rest of us.

DOWN NOT OUT

After sixteen years together, Jono Castano split from his partner, Amy, in 2021. When it comes to matters of the heart, it’s unlikely anyone goes through life unscathed, but while some relationships simply run their course, for others the end is defined by pain and anguish. Castano and Amy hadn’t just navigated adolescence together, they’d also co-founded Acero and were united in their vision of what this community could become. Theirs was a bright future with lofty ambitions, the stress of which they shouldered together. It was a relationship forged in friendship and mutual admiration, one that although amicable in its ending, left Castano reeling.

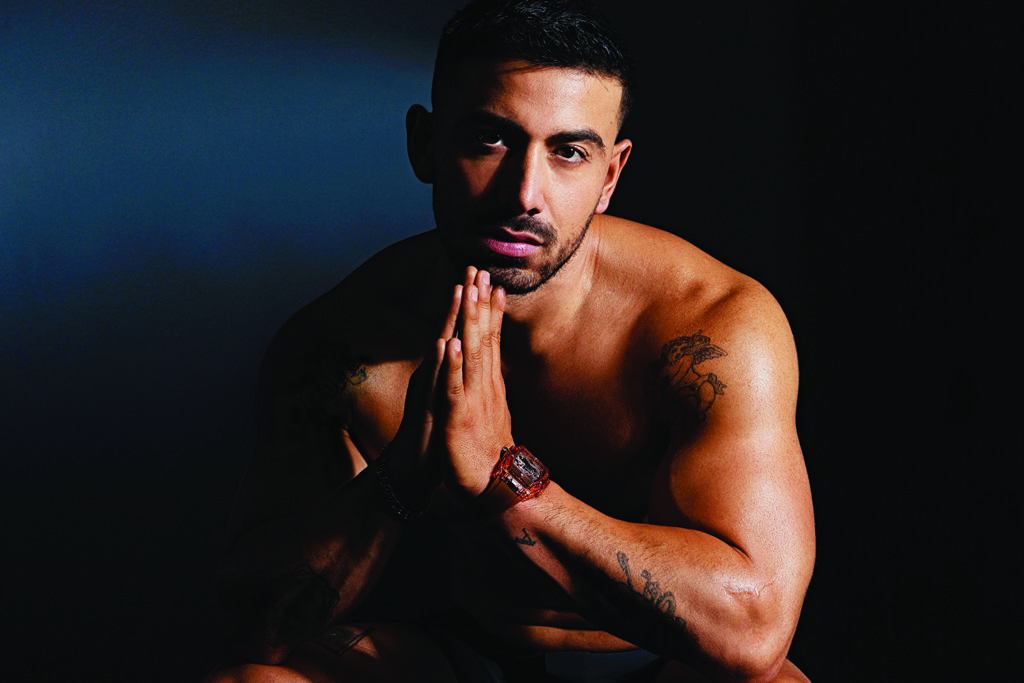

Speaking about it now, Castano’s voice is soft and still carries traces of the pain that nearly broke him. “I always say to people the three hardest things are someone passing away, someone getting really sick or getting a divorce. I experienced that. It was a crazy time. I lost who I was and put on a lot of weight.”

Not fully comprehending the extent of his emotional turmoil, Castano lost his passion for everything. As he tells me, “I didn’t even realise what was actually happening to me. It just became where I didn’t have energy for anything. I was struggling at work, cutting down my hours dramatically. I just didn’t want to be apart of it. It was full-on, it was really tough.” His weight crept up to 106 kilograms, the highest it’s ever been. Though fluctuations are always to be expected, the significance of this spike wasn’t lost on Castano. “This was far deeper than just putting on weight,” he says. “This was about losing myself and who Jono Castano was.”

SUPPORT CREW

Moving out of the house he shared with Amy, just as Australia was plunged into months-long lockdowns, meant Jono Castano struggled with feelings of loneliness. He decided to move in with his best friend, later applying for an exemption to travel that saw him take three months off to try and recalibrate. He went to Vegas, then New York and Mexico. He received a call from Sir Richard Branson’s team asking if he was available to train the British billionaire on a yacht while vacationing in Miami. Castano wasted no time in replying: ‘Yes’. He went back to Colombia, then to Los Angeles and Texas. He went to all the bars, parties and restaurants trying to bring a sense of fun and enjoyment back into his life. Then, Castano returned home and was confronted by the myth travel presents to us all: it might masquerade as a form of escape, but inevitably we all return, if not to the home we once lived, to the person we always were.

Castano knew that if he was to regain a sense of purpose, he had to reignite his passion and to do that, he needed to return to the gym. He already knew the formula and what to do to lose the weight he’d stacked on. Having trained some of the world’s biggest celebrities, he also knew the hard work required to see progress. But in going through his own transformation, Castano learned that there are limits to hard work. One can’t simply muscle their way through life at all costs. Sometimes, the stronger thing to do is to ask for help. For Castano, that breakthrough came at Acero, where a supportive network got behind him. “I was here at the gym, surrounded by amazing people, and I think having that support system is the perfect way to really find yourself again,” he says. “A lot of us in tough situations feel alone, like we can’t speak to anyone, but that’s the most important thing: anything that you’re feeling, someone is always going to listen.”

In 2021, Jono Castano’s standing in the fitness industry was well established. After whipping Michael Clarke into shape for a Men’s Health cover shoot and transforming Rebel Wilson as she embarked on her Year Of Health, Castano’s name was on everyone’s lips. But in going through his own transformation, Castano added a new skillset to his training toolkit, realising hard work means nothing if you aren’t prioritising your own wellbeing in the process. “The harder thing for me was finding the time to put in for myself and dedicate to training,” he says. “That’s something I really put into my schedule. I was like, Hey, look, I’m going to focus on myself and actually put time aside. I think a lot of people struggle to do that with any transformation; they just don’t have enough time in their day to put towards themselves because they’re too busy focusing on other things and so they forget that their health is the most valuable thing.”

There’s a lightness to Jono Castano now. It’s clear that he’s lost the 17 kilograms he gained in the aftermath of the divorce, but it’s also apparent that he’s emerged on the other side of heartbreak with a stronger sense of self. “It took a long time for me to be like, Okay. I’m okay on my own,” he says. “It’s not like a quick fix. We go through waves. I went through ups and downs. Some days I’d feel amazing and others it’s creating inner demons in me, then you feel great and back again.” He smiles.“I’m back to my old self again.”