Back in the mists of 2019, before any of us had heard of COVID or given much thought to the handling of pangolins in Chinese wet markets, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the 11th edition of its International Classification Of Diseases. Among the additions: a new definition for the term ‘burnout’.

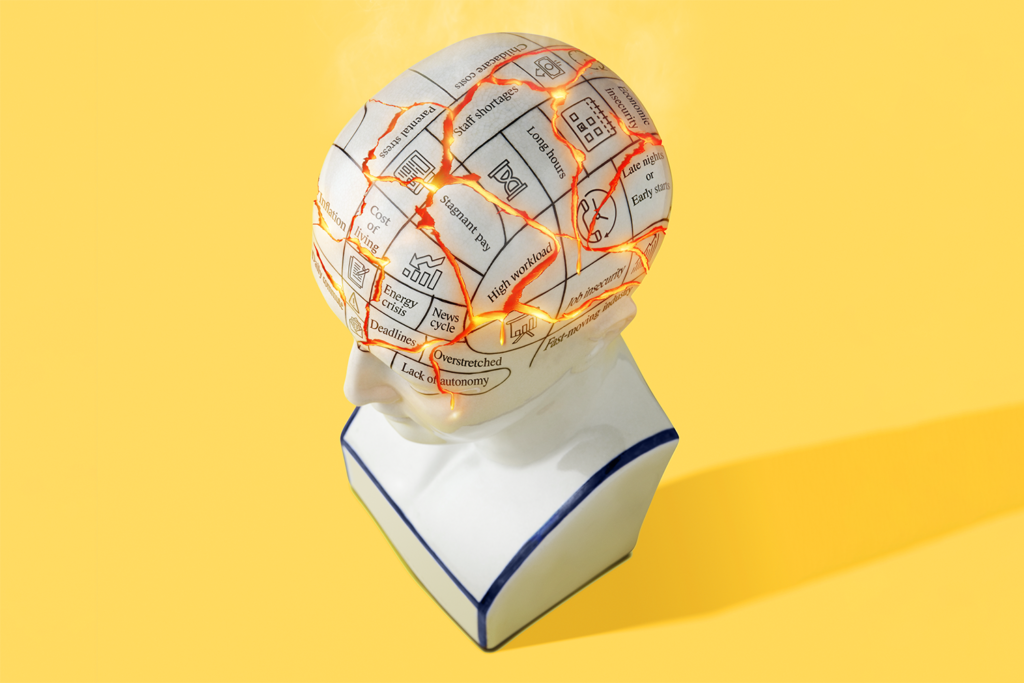

Burnout is a syndrome resulting from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”. The document carefully defines it as an occupational phenomenon – so it’s not caused by human frailty but by inhuman expectations. And it’s characterised by three dimensions: “energy depletion or exhaustion”; “increased mental distance from one’s job”, which manifests as negativity or cynicism; and “a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment”. Put simply, burnout is when you come up against the physical and mathematical limits of what The Apprentice contestants call “giving it 110 per cent”.

It was a timely addition. Looking at a few headlines in 2022, it seems that two-thirds of small business owners are burned out; 70 per cent of lawyers are risking burnout; one in two teachers reported having suffered feelings of burnout; and health workers are especially burned out, as they have to deal with the effects of everyone else being burned out while burned out. (“I think everyone is worried that the system is beginning to break,” Andrew Goddard, president of the Royal College of Physicians, said in May.) Service worker burnout is worse than ever according to informed sources; and the situation for truck drivers is no better. “It’s not a normal life for a human,” one told reporters. “It’s like a prison; it’s not a job. You do it like a zombie.” While the situation is worse in low-paid jobs, managers are affected, too. Parental burnout – when you’re so physically and mentally overwhelmed by your children that you’re a threat to their safety – is also on the rise. While the WHO’s definition warns about stress in the workplace, most parents would argue that caring for another human is work, whether you’re paid for it or not.

In short, it’s hard to find a group of workers who are not facing burnout. “Whenever we poll people about whether they’re feeling these symptoms, it’s always over 80 per cent,” says Kate Daley, a clinical psychologist who helps large companies look after their employees’ mental health. And burnout tends to lead to more burnout, too. The US, for example, has seen a so-called Great Resignation (more than 4 million people quit their jobs last September, representing three per cent of the workforce). In Australia, meanwhile, there has been more of a Great Reshuffle, as a tightening labour market prompted almost one in 10 workers to change jobs during the height of the pandemic. “We pay a lot of attention to people leaving work, but what about the people still doing the jobs?” Daley says. “They’re absorbing a lot of extra work and it’s amplifying their own burnout.”

And it’s not as though we’re out of the period of uncertainty either, says workplace psychologist Jeremy Snape (who also hosts the podcast Inside The Mind Of Champions). “So many of the threats to our wellbeing and financial security are unknowable and uncontrollable,” he says. “We’ve got the energy crisis and the cost-of-living crisis and it’s added to the latent, low-lying anxiety from the pandemic. And a lot of businesses now are trying to transform their business to meet new demands – asking people who are already burned out to be creative, collaborative and entrepreneurial when they feel least able to do it.”

Work As Religion

Burnout is not something that can be solved with a holiday or a few well-aimed life hacks. Part of the problem is the modern culture of trying to optimise every single area for maximum productivity. “That’s something we really need to challenge,” Daley says. “It’s not just about doing things as an individual. It’s caused by organisations and it needs to be addressed by organisations as well as individuals. It’s to do with high workload, lack of control, lots of uncertainty about what’s coming next, lots of change, in addition to some of the pressures we put

on ourselves.”

Her point is if you work for a company that makes unreasonable demands, they need to change – not you. But what if you are the organisation? I’m a self-employed worker [of whom there are some 2.2 million in Australia as of 2021 – or 17 per cent of the workforce, according to Independent Contractors of Australia], which means lots of change, high workload and lack of control are fairly accurate descriptions of my pre-pandemic work life. And that was before I had to do it all while attempting to home-school an eight-year-old and pacify an extremely loud one-year-old, with all the anxieties around health, income and little or no social contact. Not that I’m a special case. These past few years have been a collective nightmare, right? Whatever your own private misery happens to be, it’s likely the pandemic made it worse.

But hang on a minute. Is this burnout? Can more than 80 per cent of the population really be suffering from the same syndrome? Jonathan Malesic literally wrote the book on burnout (The End Of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us And How To Build Better Lives) after suffering from it in his former life as a theology professor. He is glad that the phenomenon is receiving wide attention but warns that, much like depression and trauma, the term is increasingly used to dramatise conditions that aren’t really burnout. “On the one hand, there’s a danger of not taking burnout seriously enough – equating it with just needing a weekend off,” he says. “On the other hand, there are those who almost take it too seriously and see it everywhere.”

However, even if we stick with the WHO’s definition, it’s clear that more and more people are heading that way. “I see burnout as the experience of being stretched across a gap, between your ideals for work and the reality of your job,’ says Malesic. “Our ideals for work are too high, generally. We expect work to do things that it can never deliver. And at the same time, the conditions at work have eroded in important ways,” he adds.

In western countries especially, Malesic believes, we have developed a quasi-religious faith in work as a source of not only security, stability and material comfort, but of identity, fulfilment, prestige, happiness, purpose, meaning. And yet we are doing so at a time of economic, political and technological volatility with wages in long-term decline, spiralling consumer debt, unaffordable housing, rampant inflation and the rest.

So, when we give it 110 per cent and it fails to yield the desired results, many of us take that as a deep personal failing – even if it’s not really our fault. The late political theorist Mark Fisher called this “the privatisation of stress”. And for many, this was made much worse by the enforced social isolation of the pandemic.

Numb To The Strain

Jack Allen, 32, had been contentedly working as a freelance animator and audio producer for a couple of years before the pandemic hit. But with a wife on maternity leave, two children at home and an uncertain future ahead, he went into survival mode during the first lockdown in 2020. He began scouring websites for tiny jobs that were well below his expertise and pitching for work with corporations that he detested. “I wanted every little bit of money I could get through the door, as I didn’t know when it was going to stop,” he says. At one point, he spent 20 hours straight animating the text on a series of karaoke videos. “It was really surprisingly labour intensive.” After the website took its cut, he’d earned about $10 an hour. This is less than half the minimum wage. But it was money.

Allen ended up retreating to his study, shooing away his children and working until 1am most nights, as well as weekends. “It would always be, ‘I just need to get through this bit’. But I never got through that bit,’ Allen says. He began to feel provider anxiety. “I was like, ‘I’m the breadwinner’. Then you get a taste of the money and that makes you want to do more. A job comes in for a couple of grand and you think, Hmm, I can probably fit that one in. But if you’re working until 1am every night, when the hell are you going to fit it in?”

“We grow up being told if we work hard, we’ll get this great life”

Then, one day, the lockdown restrictions eased and all the work dried up. Allen couldn’t understand why. But nor did he really care. “I realised I’d reached burnout. I had no drive to do anything. I’ve suffered from depression since I was 19 and it manifests as anger a lot. I was getting angry at every little thing. Young kids don’t help. But it was more like complete apathy,” he says.

Allen is not the only man I speak to who describes apathy as the main symptom of his burnout (this would be the cynicism component of the WHO definition). Stephen Mai, 39, says he has had “brushes with burnout” many times since he moved to London from Australia in 2012. It started when he landed a “dream job” at Vice Media. “When you’re doing your dream job, it’s all-consuming,” he says. “I was riding off adrenaline, getting off on hitting milestones, imagining how impressed the teenage me would have been – until one day, I realised I couldn’t think about anything outside of work.” But even when he quit the job, he didn’t stop obsessing about it. “I remember going back to Australia, and I couldn’t feel anything. I was totally numb. I said to a friend, ‘It’s like my body has shut down.”’

The friend recommended that he try hypnotherapy – which did the trick in the short term. But it didn’t stop the cycle repeating in all of his subsequent jobs. “I noticed that there was a pattern: obsession, adrenaline, numbness.” In a more recent role, Mai won three prestigious marketing awards for a campaign he had battled hard to get his company to agree to: a great personal triumph. Only he sat through the ceremony failing to feel a thing. “I thought I’d be excited. I didn’t care.”

“Even if you can’t reduce your workload, you can put buffers in place”

Looking back, Mai thinks this all relates to something he internalised as a child. “My parents were Vietnamese refugees to Australia,” he says. “I grew up being told that if you work hard and study hard, then you’d get this great life. And I do have a great life. But it’s not what I imagined. And there’s always an irrational part of me that thinks that I’m not working hard enough. I’m not doing enough. I’m not moving fast enough.” And social media doesn’t help. “You feel like everyone is doing so much better than you, so you need to work much harder to keep up.”

The apathy and numbness that Allen and Mai describe are, in fact, particularly male manifestations of burnout, says Malesic. Research shows that while women report more burnout symptoms than men, men are more likely to experience burnout as depersonalisation, whereas female burnout is more related to emotional exhaustion*. And men have a greater propensity towards parental burnout, too. “At similar levels of parental stress, men have higher levels of suicidal ideation and escape fantasies than women. Men imagine getting away from parenting,” Malesic says. He considers that both of these responses are related to “social scripts” – that is, the messages that we absorb from the wider culture. “Men are told, ‘Your purpose in this world is to support your family, go to work and not complain about it’,” he says. “You grimly shuffle to work and you grimly shuffle home, and your pay cheque defines your contribution to your family. That ethic is still with us, even though the conditions that enabled it are no longer in existence.” And it wasn’t a great ethic in the first place.

The problem, as Malesic sees it, is that work cannot possibly fulfil us in all the way we have come to expect. And the funny thing is, the same is increasingly true of parenting. “Our ideals have also increased. The standard is much higher. And the reality of raising children hasn’t improved correspondingly. There’s no point at which you can confidently say that you have worked enough or that you have done enough for your child.”

Get More From Less

So, what is to be done? Overthrow capitalism? Because burnout is not something that can be cured with a few gym sessions or a week on the Gold Coast. Rather dishearteningly, when Malesic experienced burnout at his old university, he managed to negotiate a whole five months of leave – only to find that all the symptoms returned the moment he went back. “Nothing had changed about my expectations for the job and nothing had changed about the conditions of the job. Of course I would go back to feeling the same way.”

What improved for these men? For Malesic, his wife landed a new job in Texas, which provided extra income and the chance for him to start anew as a freelancer. “It required me to change my expectations about what a career could be,” he says. For Allen, it was making the opposite move, from freelancing to a more settled role. He now co-hosts the podcast Loose Dads for the fatherhood network Dadsnet, which is more in line with his values. “I’m so happy now

I get to use my skills to help other people,” he says.

As for Mai, he reckons the pandemic saved him. He sat it out in Australia, did a little consulting here and there, and realised he was much happier working much less. “It fundamentally shifted the way I think about work,” he says. During his downtime, he had the idea for a new youth media channel devoted to wellness, which he has recently launched with ITV. It’s called Woo. He’s mindful of the cycle repeating but finally feels that everything is in alignment – and he suspects that, as a high-energy person, being his own boss will help, too.

He also detects a wider cultural shift. “When I was in my twenties, I would do anything my boss asked me to. But Gen Z seems to have more boundaries than us millennials. They know they can’t win. They’re working hard and hustling, but they’re also talking about prioritising their mental health.”

And while all the solutions are different, they share a common thread. It’s about deprioritising the importance of work in your life. Among the silver linings of coronavirus is that it has been a massive experiment in different ways of working: hybrid working, flexible working, even that improbable bit where the government paid people to do nothing – and we’re only now beginning to absorb those lessons.

“It’s shown us that work doesn’t have to be this way,” says Daley. And even if you can’t significantly reduce your workload, you can put buffers in place. Take rest seriously. Schedule downtime, if you have to. And build a network of people in a similar position to you, as you might be able to help them, too. “A lot of the time, burnout is really about balance,” she says. What is enough? Maybe running at 80 per cent is better than 110 per cent. “It’s often really surprising to people that when they lower their sights, they can do much more.”

As a former athlete, Snape feels we should be working in much better alignment with our bodies’ natural rhythms. “We should schedule our most cognitively demanding tasks into the time slots when we have the most natural energy. I’m not as good at 9am as I am at 6pm. For other people, 8am might be their peak productivity.” Work with your circadian rhythms and you might be surprised at how much you can get done in a relatively short space of time.

Malesic, on the other hand, reaches for a word that has all but disappeared from the language around work: dignity. “In the Anglo-American world, we tend to accord people dignity only if they have paid employment,” he says. “But people should be accorded dignity just by virtue of being a human. We shouldn’t need to prove ourselves through our work. We should have the confidence to say: ‘I matter. I am valid. I deserve to have a say regardless of my work’.”

Amen to that.

Are You feeling Burned out?

Fatigue and frustration are both fairly normal. If you’re unsure on which side of the line you stand, ask yourself these key questions:

1. Do you begin and end most days feeling physically and emotionally exhausted?

2. Do you feel a persistent sense of cynicism? That everyone and everything disappoints or frustrates you?

3. Have you started to lose empathy for your colleagues or clients?

4. Do you sometimes feel trapped, as though you lack agency

in your daily life?

5. Have you or the people closest to you expressed concern about a change in your habits, whether that’s increased drinking, smoking, eating or other compulsive behaviours?

6. Do you struggle to finish tasks you used to feel manageable or find yourself procrastinating to an unhealthy degree?

7. Do you find yourself in crisis mode more often than you used to? Do you overreact to minor changes to plans or assignments?

8. Are you feeling physically ill more frequently? Do colds come on after the big deadlines?

Answered ‘yes’ to four or more questions? You might be experiencing burnout. Speak to your boss, your GP or contact a therapist if you’re concerned.